Poetry and other words

One of several decorated rocks that appeared in my neighborhood during the early days of the COVID-19 lockdown. (Click to enlarge.)[/caption]

That’s not the perfect analogy, as we are the ones who empower government, which isn’t the same relationship as children have to their parents. In reality, it’s up to us to tell government how we should be governed. Unlike some who see government as an interference (except when they want government to make it more profitable to run a business), I have always seen the primary purpose of government to be to save us from ourselves. We use it to act as the prefrontal cortex to rein us in when the amygdala is screaming at us to fight or flee. Instead, the message from the forebrain is, “We can do this.”

My way of accomplishing both goals—working to save life on earth as we know it, and to enlist the help of government to accomplish that, is to be an active member of Citizens' Climate Lobby. But there are many ways. What's yours?

One of several decorated rocks that appeared in my neighborhood during the early days of the COVID-19 lockdown. (Click to enlarge.)[/caption]

That’s not the perfect analogy, as we are the ones who empower government, which isn’t the same relationship as children have to their parents. In reality, it’s up to us to tell government how we should be governed. Unlike some who see government as an interference (except when they want government to make it more profitable to run a business), I have always seen the primary purpose of government to be to save us from ourselves. We use it to act as the prefrontal cortex to rein us in when the amygdala is screaming at us to fight or flee. Instead, the message from the forebrain is, “We can do this.”

My way of accomplishing both goals—working to save life on earth as we know it, and to enlist the help of government to accomplish that, is to be an active member of Citizens' Climate Lobby. But there are many ways. What's yours?

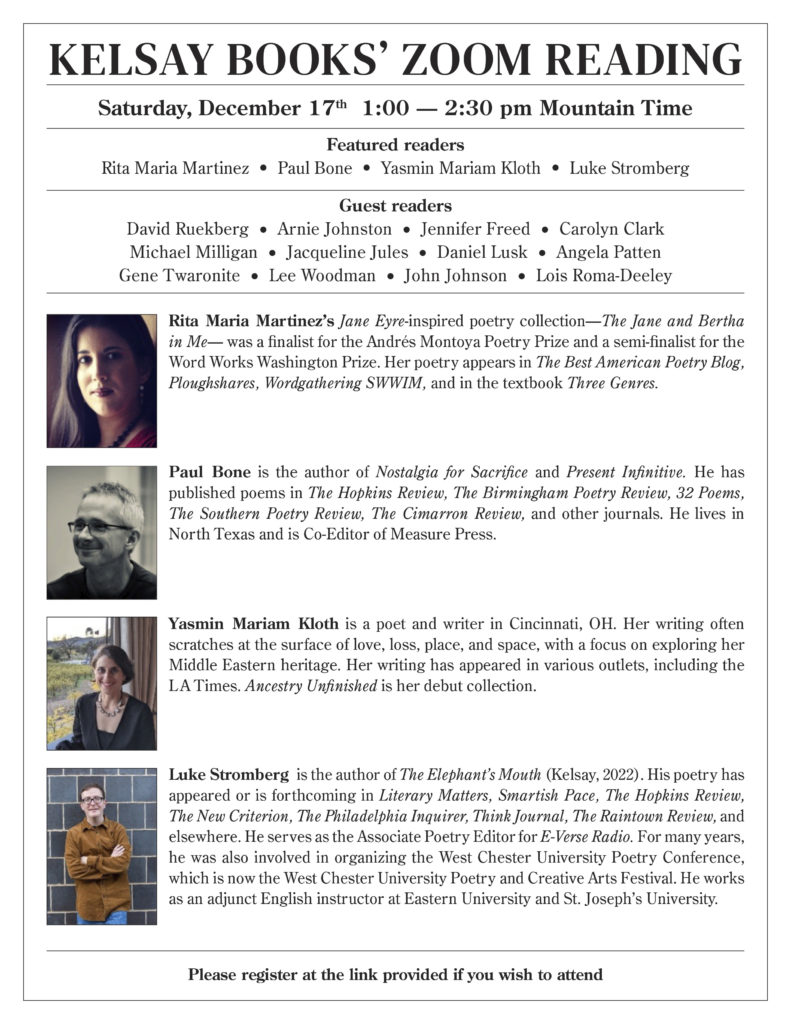

Join me and other Kelsay Books poets for an online poetry reading from anywhere! I'll be reading from my first book, Where Is the River Called Pishon?, published by Kelsay Books in 2018.

I'll be the first Guest Reader after the first Featured Reader, Rita Maria Martinez.

Please contact me for a Zoom link (and let me know you're a poetry-loving human, just so I don't share with hackers). Thanks!

Writer’s block: Is there such a thing? William Stafford’s solution: Ignore “high standards” and get into action. Expecting every draft to say it all is a lot of pressure. Instead, exercising our writing muscles every day can help prepare us for when the big poem needs to be born.

In this poetry workshop we’ll explore ways to move through fear and doldrums. Criticism—especially from the worst critic of all, one’s self—will be banished in a kind but firm manner. We’ll spend a little time discussing ways to get unstuck, produce a piece of writing, and go home with some strategies for getting unstuck again.

Register at Writers & Books . You will receive a Zoom link from them before the workshop.

This two-hour workshop is in-person at Writers & Books, Rochester, NY.

Please contact me if you have any questions.

A few years ago I started a writing project called Weather Report, about internal and external weather: the changing landscape of my spiritual evolution/dissolution, and global warming. It seems like a lot to roll into one ball, but you understand that one can't really separate the environment from what one is.

However, this post is not about that collection, which languishes in various slush piles. The lack of attention did cause me a brief period of despair and self-doubt, but against or despite or irrelevantly to my will, I found myself working in a form I call "Little Coffins." In about a year's time I found I had written about 45 poems mostly on purpose which I collected into a new manuscript I'm calling Marble and Rasp.

The name I gave the form doesn't so much have to do with my despair and self-doubt as with the shape of the poems: They appear in a rectilinear layout created by using a monospaced font and the same number of characters per line to create a poem that is right-justified without tracking or kerning. That's one reason I call them little coffins. They're boxy (most of them; see below). In terms of craft, the form puts pressure on the ideas, a little like a sonnet, but without a rhyme scheme, meter, or length constraints.

The first time I heard of this form was thirty years ago in a poetry workshop at Writers & Books, our literary writing and reading center in Rochester, NY. The instructor told us he had spent a week with another poet holed up in a house in the desert just writing. One day they challenged each other to only write poems that were completely justified on both margins. They were doing this on typewriters. I think he presented it to us in the same way Stephen Dunn once explained his tendency towards tercets--as a “compositional strategy.” At the time I thought it was a dumb idea.

In January, 2021 I went out for a winter day’s walk. I sometimes compose out loud while I’m walking, recording on my smartphone. I was looking at the clouds and the crust of snow outlining the suburban landscape and the dendritic trees against the atypically blue Rochester skies and the poem “Emendation” sprang out of my mouth. The next morning I typed it up, and wholly by accident the way I broke the lines they were almost perfectly right-justified. So I tinkered with the poem to make them align. Then I remembered the dumb exercise and laughed.

That June, attempting to protect my garden from marauding woodchucks, I accidentally caught a rabbit in my Havahart, and the next day her kitten. “Object Lesson” sprang out all of a piece, aligning on both margins with only minor tinkering. After sending it off to my writing group, I dismissed it as a lark. In September I wrote, “Object Constancy,” and something in the poem seemed to beg to be crammed into this form. I think it was the way they had a recognizable structure: introduction, development, conclusion, but without obvious logical hooks. Then “Slot Canyon” emerged, kind of on purpose, and I was off.

Fortunately, I have the advantage of a word-processor rather than a typewriter, which makes it a lot easier to edit. I realized after sending out “Emendation” that it might drive editors crazy to make my fonts accord with theirs. I realized this form would require composing in a monospaced font (like what you had on old typewriters, and which “Courier New” imitates) so that everyone (author, editor, typesetter) agreed about line length. I had typed up “Emendation” in Garamond, my preferred font, so it took some editing to make it conform. In fact, it was one of the hardest poems in this collection to align, since I had really liked it the way it was. But writers get used to merciless revision.

When I get stuck for the right line length I refer to the Thesaurus, and the site RhymeZone.com, which has a filter to let me search synonyms by word length, but most of the time I have to fall back on my own ingenuity to get not only the right number of characters in a line but also the right words.

I call these poems “little coffins” partly because of their shape, and partly for the reason suggested in the line from “Object Constancy”: “Words are shadows that mime shadows on a wall,” a twisted allusion to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. There’s the ideal reality, then there’s our perception of reality, then there’s our expression of our perception, three degrees removed from the ideal.

Towards the end of the manuscript some of them have a ragged last line. I'm not going to say why here. If it ever gets published maybe you will come up with a theory if you read it.

I tried to find out who that instructor was. For some reason I thought it was Campbell McGrath, but he responded to my email very politely and firmly that he had no idea what I was talking about. After discovering The Meadow in the Vermont home where I was sitting Fitzie, Anni MacKay and Doon Hinderyckx's Tibetan Terrier, it seemed sure that it was James Galvin who told the story of the typewriter exercise. I wrote to what I thought might be his email address, but either I was mistaken, or he ignored me, or something came up. At any rate, I still don’t know who it was for sure.

So far I've gotten one of these published. It's currently the second poem in the collection, "Weaver" (below), which I initially wrote in Ross White's September, 2021 Grind which was published in The Orchards Poetry Review. They weren't able to use a monospaced font as I had hoped, due to layout constraints, but were able to approximate the effect by manually adding spaces.

The Orchards happens to be published by Karen Kelsay, who also runs Kelsay Books, which published my first book, Where Is the River Called Pishon? A coincidence, I'm sure. Thanks to Karen Kelsay and the rest of the staff at Kelsay Books and The Orchards!

Writer’s Block: Is there such a thing? William Stafford’s solution was to ignore "high standards" and "get into action." Exercising our writing muscles without fear of “doing it wrong” helps prepare us for the moment when the “big poem” wants to be born. In this workshop we’ll play with ways to move through the doldrums and dread, including journaling, experimenting with forms, collaborating, and more.

Although the focus will be on poetry, strategies for "getting unstuck" apply to all manner of writing.

Meets four Mondays, July 18 through August 8.

Registration deadline: Friday, July 15

Tuition

Join us in raising money to provide humanitarian aid and medical relief to injured Ukrainians. Listen in as local poets (including me) read selections from Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine, an anthology of emerging and established Ukrainian voices charting what it means to be in a state of war and how it affects the poetics of a country. Sonya Bilocerkowycz, author of On Our Way Home from the Revolution: Reflections on Ukraine, kicks off the evening with introductory remarks. All contributions go to RocMaidan.

Buy your books at Ampersand and join the conversation. 30% of your purchase of Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine will be donated to RocMaidan.

This is a hybrid event held at Writers & Books, 740 University Ave Rochester NY and streamed via Zoom.

Masks and proof of vaccination are required for on-site attendance.

Hybrid Event | Click here for tax-deductible tickets @ $10, $15, $25

Writer’s block: Is there such a thing? William Stafford’s solution: Ignore “high standards” and get into action. Expecting every draft to say it all is a lot of pressure. Instead, exercising our writing muscles every day can help prepare us for when the big poem needs to be born.

In this poetry workshop we’ll explore ways to move through fear and doldrums. Criticism—especially from the worst critic of all, one’s self—will be banished in a kind but firm manner. We’ll spend a little time discussing ways to get unstuck, produce a piece of writing, and go home with some strategies for getting unstuck again.

Register at Writers & Books . You will receive a Zoom link from them before the workshop.

This two-hour workshop is in-person at Writers & Books, Rochester, NY.

Please contact me if you have any questions.

On Saturday, April 2, I’m participating in the first-ever Syracuse YMCA’s Downtown Writer's Center Write-a-Thon. I’ll be writing from sun-up to sun-down! If you sponsor me, your money will go to a good cause: the YMCA subsidizes $2 million in free or reduced memberships and program scholarships every year!

As a thank-you for your support, I will give you one of the following:

BONUS! BIG HUG next time I see you! (optional)

Click here for more info, and to donate. Thanks to those who already have. We're getting closer to our goal!

Image is often thought of as a picture in the mind, although any sensory experience counts. Ezra Pound defined image as “that which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time.” It’s the flash of epiphany—what makes us go “Ah!”

And yet poems are made of sentences, or parts of sentences--one word after another. In this class we’ll look at the way words, lines, and sentences prepare the way for moments of increased awareness. Through discussion and brief written commentary you will observe how poets as diverse as John Keats, Yehuda Amichai, Brigit Kelly, Reginald Dwayne Betts, and others wrangle with this interplay.

Participants will generate new writing and discuss it in workshop in the same way we discuss published work: noticing how it’s working, rather than “fixing” other people’s poems. First rule of workshop feedback: Respect.

Meets eight Tuesdays, April 26 through Tuesday, June 14

Registration deadline: April 20

Tuition

Please join me and four other fine writers as we cap off a day of talks, workshops, and readings at Writers & Books' Virtual Literary Conference. Enjoy poetry, fiction, and hybrid forms by Makalani Bandele, Sarah Freligh, Anastasia Nikolis, David Ruekberg, and Holly Wren Spaulding.

The conference theme "Taking Care in Writing, Publishing & Building Community" addresses the question, "How do we carve out purpose, chart a meaningful course, through troubling times that don’t seem to end?" The keynote address will be presented by Kwame Dawes, speaking on Literary Citizenship.

Access to this reading is included with your purchase of a conference pass: Early Bird Rate: $195 (valid through January 13) | January 14 – 23: $225

Please join me and four other fine writers as we cap off a day of talks, workshops, and readings at Writers & Books' Virtual Literary Conference. Enjoy poetry, fiction, and hybrid forms by Makalani Bandele, Sarah Freligh, Anastasia Nikolis, David Ruekberg, and Holly Wren Spaulding.

The conference theme "Taking Care in Writing, Publishing & Building Community" addresses the question, "How do we carve out purpose, chart a meaningful course, through troubling times that don’t seem to end?" The keynote address will be presented by Kwame Dawes, speaking on Literary Citizenship.

Access to this reading is included with your purchase of a conference pass: Early Bird Rate: $195 (valid through January 13) | January 14 – 23: $225

Join me and Central NY poets as we present our prose poems, hosted by the Cayuga Museum of History and Art. I’ll be reading from my most recent book, Hour of the Green Light, and from Weather Report, a work in progress. Click here to read more, and view on Facebook or Zoom.

Join me and Central NY poets as we welcome spring with a reading of poetry hosted by the Cayuga Museum of History and Art. I'll be reading from my most recent book, Hour of the Green Light, and from a work in progress. Click here to read more, and view on Facebook or Zoom.

I’m up at the Salon in the February slot reading four poems from Hour of the Green Light in various settings. Enjoy!

I’m up at the Salon in the February slot reading four poems from Hour of the Green Light in various settings. Enjoy!